|

DIVERSION is a magazine for Physicians. Michael Greenspan has a software company in NYC. |

HIS DREAM CAR

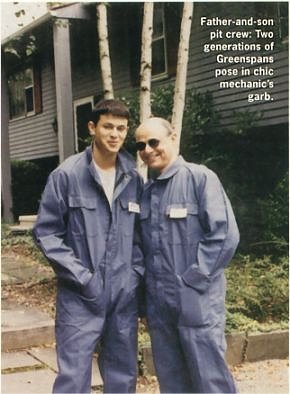

A father and son find common ground

over, by Michael Greenspan September 1966, Los Angeles. I was standing in front of Carroll Shelby's car showroom, about to hand someone the papers for my new Mustang GT350. I went into the showroom, and there they were: two 427 Cobras. I knew I couldn't afford one, but if only... For the next 30 or so years my wife would periodically put up with my mumbled "Someday I'm going to have a, you know, a Ferrari, a Lamborghini." The unsaid name was Cobra. It was too out of the question. |

|

| Then, some years ago, at the invitation of a friend, I took

our son, Joshua, to the Lime Rock Racetrack in Connecticut. It turned out

to be a Carroll Shelby Cobra weekend. The other cars were swell, but the

Cobras were amazing. Maybe Joshua got bitten, too. I don't really know. He

was brought up in New York City and at the age of 19 still didn't have a

driver's license, so I didn't think he cared too much about "real" cars.

After he chose to go to Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, I mused aloud, "Well, now that you're only going to be twenty-five minutes away from our house, maybe we'll build a replicar." Imagine my surprise when his instant reply was, "Of course, it has to be a Cobra." "Replicar" is a term that describes a car built to merge the best of what was with the best of today's engineering knowledge. Another option is a kit car, which is a donor car mated with a fiberglass body (like putting a Ferrari-style body on the chassis of a Fiero). Neither a replicar Cobra nor a kit Cobra could be defined as a real Cobra. A real Cobra would be about 35 years old and would cost an enormous amount of money. What I wanted was a time machine: a car with a modern chassis design and mechanical systems built from the ground up, one that was as close in spirit to the real Cobra as was realistically possible. A replicar is built with that philosophy. Beyond that, I thought of the project as a father-son thing. Show the kid what cars are all about. Share the grease stains and scraped knuckles. So I went on a hunt to find out what was available and discovered that one of the best Cobra replicar companies, ERA Replica Automobiles in New Britain, Connecticut, was also about 35 minutes from our house, and only 10 minutes past Wesleyan. I visited, anguished over whether or not to take the plunge, and in November of '97, placed the order. |

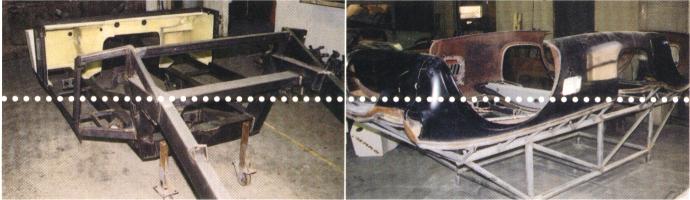

Greater than the sum of its parts: The Cobra's chassis (left)

and the body (right) wait to mate in ERA's garage.

| By then we had decided that, for us, building a car did not mean welding

the chassis or grinding the valves or lots of other basic stuff. It meant

that we would have ERA build the basics to our specifications (which should

take around seven months and be ready in June), getting us to the

three-quarters-complete stage. Then we would do enough to feel true

ownership.

What we didn't bargain for was the relationship that would grow during the time we waited for our car to be constructed. Car details began to take up most of our telephone conversations: "Which wheels?" "Which valve covers?" "Do we want the AC logo or the Cobra snake?" were stuffed in alongside "How's the art history paper coming?" It was easier to have conversations when they didn't always start with "How was the test?" The one item both of us and my wife agreed upon from the start was the color. ERA had a silver car that was being shipped to Germany, and to all of us it was just gorgeous. So we knew we wanted silver. But until someone asks "Exactly which silver?" you can't imagine how many different shades of silver there are. Finally, we pointed to a car and said, "Just like that." We got involved with people who were fanatical (in the best way possible) about what they did. Our Saturday morning treks to ERA were always rewarded with learning about another obsessive owner or soon-to-be owner. It reminded me of going to the barbershop on Saturday mornings as a kid. This was "guy talk." Joshua listened to people who had spent five years accumulating all the right parts to build the right engine before ordering a car. What amazed both of us was the egalitarian spirit. You could be a mechanic or a bank president; it didn't matter. Loving Cobras did. The drives back to school were taken up with conversations about the fun and the obsession we were now a part of. Sure, Joshua learned what disc brakes were and how they worked, but I think he also learned about and developed respect for other people's dreams. As the months went by and the wet summer stalled the paint job, it seemed that June was only a wish. Indeed, June and July slipped away, and August became our new due date. Time was running out-I had business obligations, and Joshua would be starting a new term at college. Peter Portante, the general manager at ERA, broke the news as gently as possible: The car would be ready the last week of August. I told him that would leave us only a couple of weeks to do the work. "It can't be done," he said. "You can lose a day if one piece doesn't fit fight." We worked out a compromise. Joshua and I would come to ERA and work with its mechanics to get the major assemblies-engine, trans- mission, and exhaust-in place before they trucked the car to our house. It worked. On August 29 the mostly completed car was carefully lowered off the flatbed onto our gravel driveway. It was a beautiful day, and we all just seemingly froze for a moment or two as the reality dawned on us-there was a Cobra in the driveway. Now it was time to see if we could make it work. We carefully rolled it into the garage, which was clean and ready. |

Left: Look, Ma, no wheels! The Cobra bares its naked

axle. Right: The Greenspan's dream get fit and finished.

| A small aside: Joshua and I do not work well together. However, I had

hoped this would be an adult project that would change that. We unloaded

all the boxes of components, set out the tools, covered the fenders with

protective throws, and began.

The engine compartment wiring was first. We took turns reading the instructions and putting things in place. So far, so good. At the end of the second day we were done with the engine compartment and the dashboard. Now the scary part: Turn the battery on. I flipped the switches one by one; they all seemed to work. Now for the brake lights. Oops! I thought the people at ERA had wired the back lights, but they hadn't, so I blew a fuse. I lost three hours trying to find a shop with a replacement on a Sun- day. Gas stations now sell milk and cookies but not fuses. We finally found a store that had an auto section with fuses in abundance. We loaded our pockets and returned to the garage. I traced the wires and hooked up the lights, and we were in business. Then came the moment of truth. I turned the key to see if the engine would start. The engine didn't slowly turn over and make the usual whir. Rather, it exploded to life. It was as if the eight cylinders had been rudely awakened and couldn't wait to get on the road. It was a Sunday night with still plenty to do-the interior, the doors, the seats, et cetera-but that could wait. I grabbed a seat and put it into the car. Joshua was puzzled. "What are you doing?" he asked. I told him I was going for a ride. "Not without me," he said. He jumped over the car door and sat on the aluminum floor pan. We slowly drove out of the driveway and then up and down the cul-de-sac where we live. The little kids all gave us the thumbs-up. It seemed a shame to have to return to the garage to do the rest of the work. Back inside, we removed the doors and went back to finishing the interior. We established a rhythm: One of us painted on the adhesive, then the other carefully did the installation. We almost forgot to take pictures. Bad for the memories, but a good sign of work involvement. The most difficult parts turned out to be carefully bending the aluminum doorsill molding and screwing it into place. The screws are very delicate, but Portante had warned us and suggested a technique that worked perfectly. Finally, we put the seats into place and glued the rubber weather stripping on. It went smoothly, and by Wednesday night we were looking at our finished Cobra. In October, on my 55th birthday, Joshua and I drove the car to Brooklyn. Going south on Fifth Avenue, he said, "Pop, watch the reflection in the windows as we drive by." What I saw was a very happy father and son riding in one heck of a fantasy. If you are interested in kit cars or replicars, you can contact ERA Replica Automobiles; 608-612 East Main Street; New Britain, CT 06051; 860/224-0253; or check the Web at www.erareplicas.com. |

| For Joshua's view of the Cobra project, see the next page. |