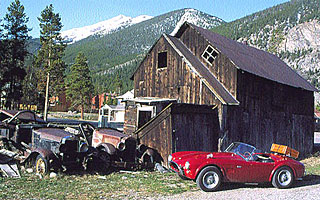

I flew from Wisconsin into San Francisco on a warm, sunny day in May, and Tom picked me up at the airport in an Audi wagon belonging to Jacques Harguindeguy, the man who had owned the Cobra for the past seven years. Jacques and his wife, Betty, had put Tom up overnight while they signed all the papers, and Tom handed over a check for “more than $100,000, but less than $200,000,” as he would tell the bluntly curious during our trip. When we pulled into the driveway of the Harguindeguys’ home, Tom opened the garage door, and there it was. A beautiful car in deep, dusky red, top down, poised for the trip. Much as I love the MGs, Healeys and Triumphs of the same era, there is something quite different about a Cobra, some quality that always makes the hair stand up on the back of my neck. The car bristles with subtle chrome details overlaid on a set of beautiful curves, and it gives off an aura of aggression that few other English roadsters possess. It looks vaguely like some sort of Medieval weapon, as though the apparently harmless snaps across the back deck for the car’s top might be the points of a mace that could be wielded on a chain. The Cobra, like certain Ferraris, has both beauty and brutality in its lines. When Carroll Shelby chose the AC chassis and body to contain his hard-hitting Ford drivetrain, he chose well. With a few snapshots and handshakes, we slathered ourselves with sunscreen and were ready to go. Just like that; off the westbound plane and into an eastbound Cobra. Tom climbed behind the wheel and I reached inside the door, pulled down on the leather latch-string and slid into the passenger seat and looked around. Here was one of my favorite cars of all time, yet I’d never so much as sat in a 289 Cobra. Comfortable leather seats (well-broken-in originals), lots of leg room, wide, aviation-style lap belts, a full panel of American Stewart-Warner gauges, dished wood-rimmed wheel, Mustang-style 4-speed shift lever with the lift-for-reverse T-handle under the knob. Volkswagen turn-signal and horn lever on the right side of the wheel. Roomy side-pockets in the doors, a nice big glovebox in front of the passenger. Knobs and heater controls right out of my dad’s 1962 Falcon station wagon. The sight of them almost made me dizzy, like the strong aroma of perfume nearly forgotten from an early date in high school. “What’s this?” I said, pointing to a small toggle switch on the dash. “I think it’s for the electric radiator fan,” Jacques said. “I just leave it on.” Tom pulled out the Falcon choke knob, turned the key and the 271-bhp Ford 289 V-8 whomped immediately to life in a mellow, loping cadence. I turned to Tom and grinned. “Wonderful sound, isn’t it?” he said. “Wait’ll we get out on the road. This thing sounds like a Chris-Craft with underwater tailpipes.” Indeed it did. Road music. As we moved into traffic, Tom tapped on the instrument panel and said, “No tach. I didn’t have time to get it fixed.” We pulled into a local gas station to fill up, and a mechanic who had done maintenance work on the Cobra came out and wished us luck on our trip. He also offered a final benediction: “If you have car trouble,” he said with mock solemnity, “may you have it far away from here.” Tom drove into the gathering snarl of rush-hour traffic on I-580, slowing to walking speed, with the temperature gauge crossing the 210 mark toward 220, but it never steamed or coughed up any water. A sign on a bank near the freeway said it was 96 degrees. The cockpit, with its thin layer of carpet, was plenty warm, but not shoe-melting hot. |